8 Tips for Pragmatic Technical Decision-Making in Fast-Paced Environments

This blog post explores the engineering decision-making challenges in fast-paced development environments, the importance of maintaining technical agility, and presents a framework to make balanced technical decisions that enable consistent velocity and quality.

Introduction

In the software engineering industry, it’s almost inevitable that, at some point, we’ll be working with tight timelines. For some, this is the standard way of working.

Frequently, tight deadlines can result from bad planning and wrong estimations. While unrealistic timelines are always a problem, sometimes, timelines can be tight by design.

One of the most common and arguably successful approaches to building digital products is product-driven development1. Product-driven development is a user-centric approach aligned with the agile philosophy that uses quick rounds of experiments to discover value and adjust accordingly. This makes a fast-paced environment the usual way of working.

Engineering teams face a significant challenge in such fast-paced environments. We need to make the correct technical decisions to deliver high-quality software while being pressured to deliver quickly for early feedback. On top of that, these decisions are often made with limited knowledge and many assumptions.

These decisions are often vital for a company’s survival and success. And even when time is not crucial for the company’s survival, a wrong technical mindset in a product-driven environment can waste money and time on things that are later proven not to be valuable or delays that hurt competitive advantage.

In this blog post, we see in more detail what is Engineering’s role in product-driven development, the importance of technical agility, and a set of guidelines to approach technical decision-making that enables us to move effectively and efficiently through a fast-paced loop.

Product-driven software development

To understand what we need to do from an engineering perspective, we need to understand the macro-level end goal of what we are trying to achieve.

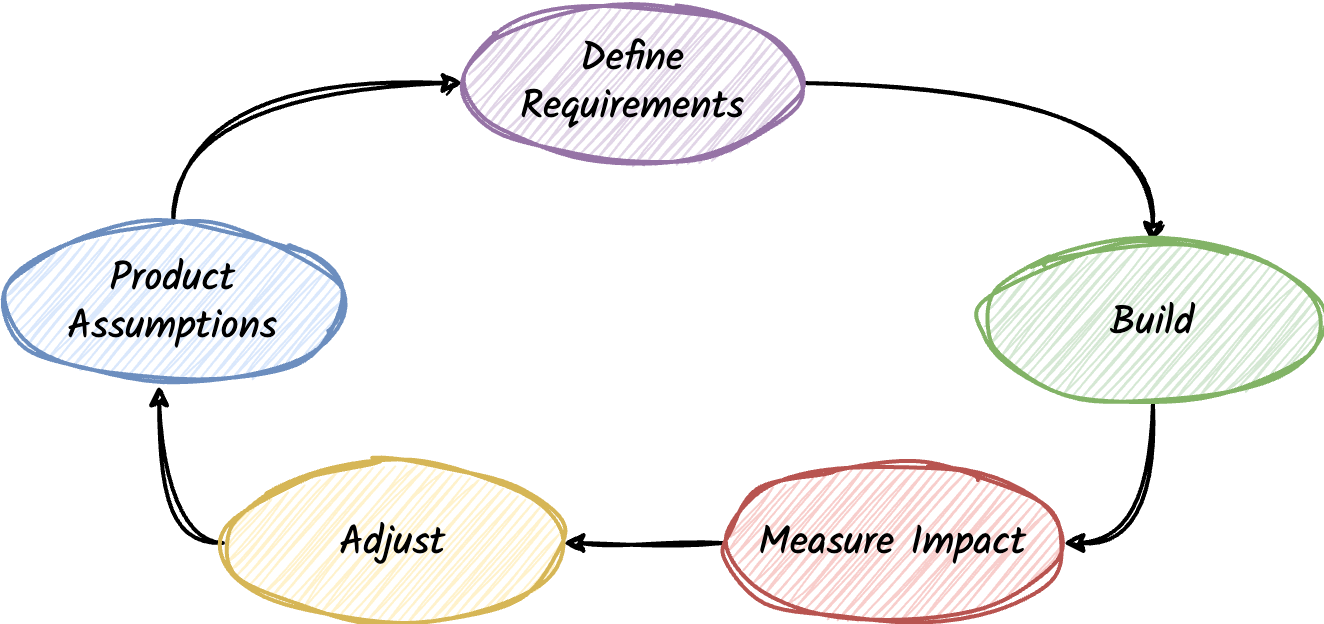

The main idea behind product-driven development is that the focus is on the user, and the approach in which we make decisions and adjust is based on a feedback loop that looks like this:

-

We have an idea. We make assumptions about the idea’s usefulness and resonance with our audience. We explore the idea a bit more and do some product discovery

-

We form some requirements based on the product discovery

-

We build the feature/product based on the requirements

-

We measure the impact of the introduced feature

-

We make the necessary adjustments

-

Repeat

The goal is a fast flow with quick feedback. We want to make the above loop as quick as possible. We don’t want to waste time and money on things that may not work.

We build something fast, we get feedback, and we adjust.

If it is successful, good; let’s build on it.

If it’s not, no hard feelings; we throw it away and try something else.

The Role of Engineering

In a product-driven flow, the software engineers’ role is to build the product.

From a product perspective, the engineering team is expected to

-

Deliver the product requirements correctly and

-

Provide it to users as early as possible

Engineering challenges

The above requirements may seem straightforward and obvious, but during this continuous feedback loop, everything, including the technical side of things, is based on unverified assumptions.

Unverified assumptions and requirements influence the engineering decisions. A rigid solution on highly uncertain conditions that later proved to be wrong, can be a tremendous blocker to the growth of the software.

The project is doomed if we don’t have a solid framework for decision-making for high uncertainty and continuous change.

The importance of technical agility

From an engineering perspective, the core goals are, of course, aligned with the product goals: quick, correct delivery. However, that’s not enough.

Uncertainty/assumptions and the state of the codebase play a significant role in the engineering’s ability to deliver correctly and quickly. We also need to do this consistently.

If we want consistent quality and quick deliverables under high requirement uncertainty, we need technical agility.

Technical agility is the property of our software that encapsulates a set of attributes that give us the ability to move quickly, with good quality deliverables, while being ready to adapt if needed based on multiple assumptions and limited knowledge.

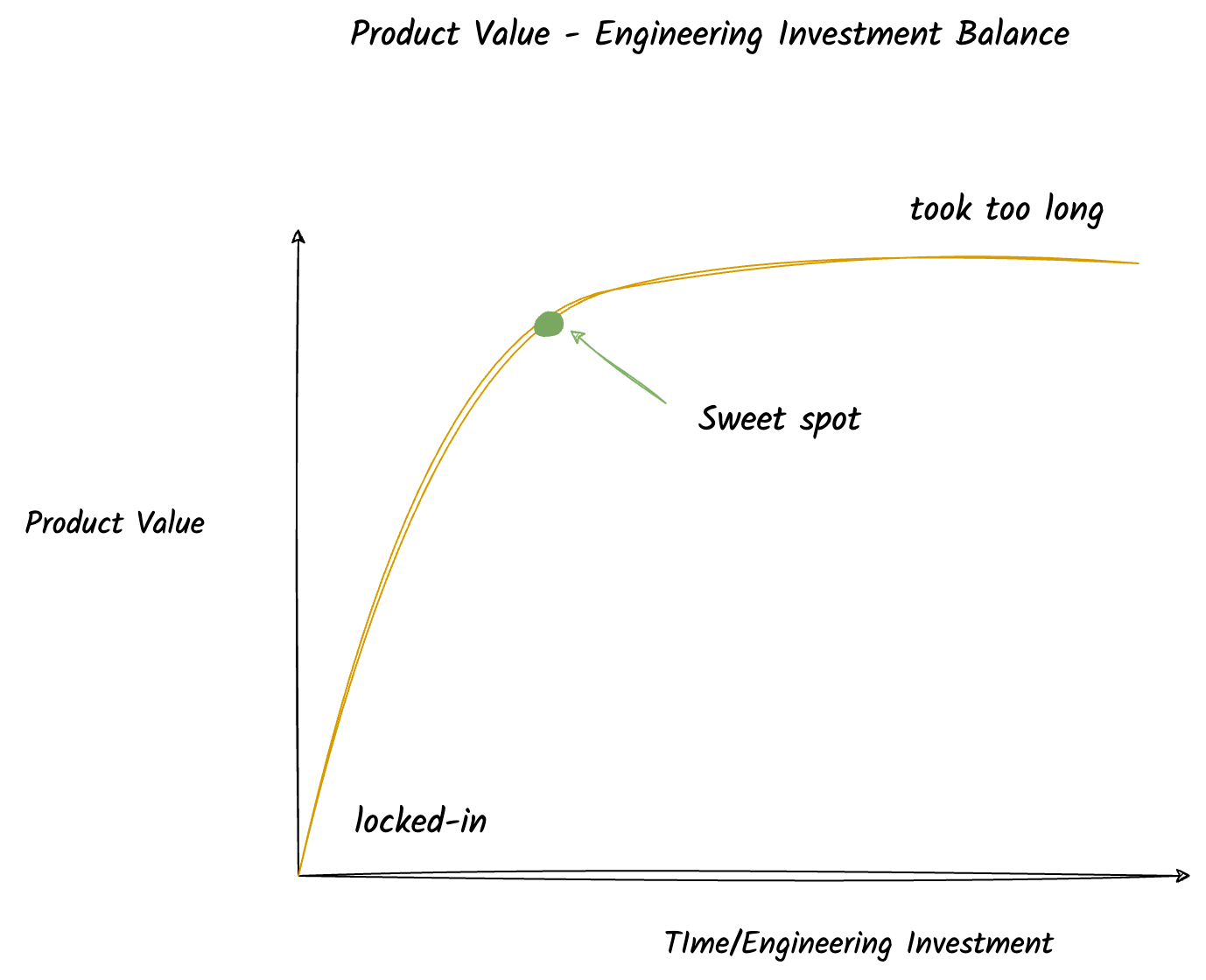

Balancing between product value and engineering cost

For a sustainable flow, our ultimate goal is to optimize the engineering cost VS product value. How do we do that? We need to aim for:

- A software that does what is expected to do while

- Balancing between

- The Time-to-market.

- Adaptiveness to change.

The two sides in the balancing spectrum are the “locked-in” and the “over-investment.”

- Locked-in

- You end up in a dead-end because of the limiting technical decisions that only allow you to move slowly if your experiment is successful.

- Your MVP did well and proved to be successful. However, your next requirements are only possible to build if the underlying technical foundation supports them.

- Over-investment

- You have dedicated too much time focusing on quality and making the super duper extra wow extensible architecture but

- It’s too late. You missed the competitive advantage, or you are out of money.

- The experiment didn’t work out - you need to throw your idea and start a new one.

- You have dedicated too much time focusing on quality and making the super duper extra wow extensible architecture but

Being locked in is usually a better problem to have; however, depending on the size of the problem and the pressure, it might inhibit the product’s future success.

Conversely, over-investment is inefficient and can kill a product/company, especially if it has a limited budget. If something could be available for feedback equally well without that much extra cost, there’s room for optimization.

A pragmatic, technical decision-making framework

Decision-making in an environment full of unknowns is always challenging. We need a system, guidelines, a focus, and something to optimize for.

As we saw in the previous sections, we must ensure correctness while balancing adaptability and time-to-market.

We can think of these decision-making guidelines in three main dimensions:

- 🚩 Direction

- Foundational guidelines that affect every decision in this framework.

- ⚖️ Quality Management

- How to manage and follow up on quality decisions.

- ⏩ Decision speed

- Move quickly; unblock yourself.

Below we will see a set of guidelines that I have been following as a Technical Lead and an Engineering Manager to make decision-making more systematic. These guidelines have been serving my teams well, especially in high-pressure times:

-

🚩 Define your focus in an ever-changing environment

-

🚩 Concentrate on what you know now, don’t think too far ahead

-

⚖️ Enforce a non-negotiable Quality Baseline

-

⚖️ Keep it simple

-

⚖️ Embrace quick, correct, sub-optimal solutions

-

⚖️ Carefully Track and regularly review tech debt

-

⏩ Move fast through two-way doors

-

⏩ Avoid analysis paralysis by time-boxing, accept mistakes

Let’s explore them in more detail.

1. Define your focus in an ever-changing environment

Our overall goal is clear; We need consistently quick, correct deliverables. And as we’ve seen, we can achieve this by striving for technical agility.

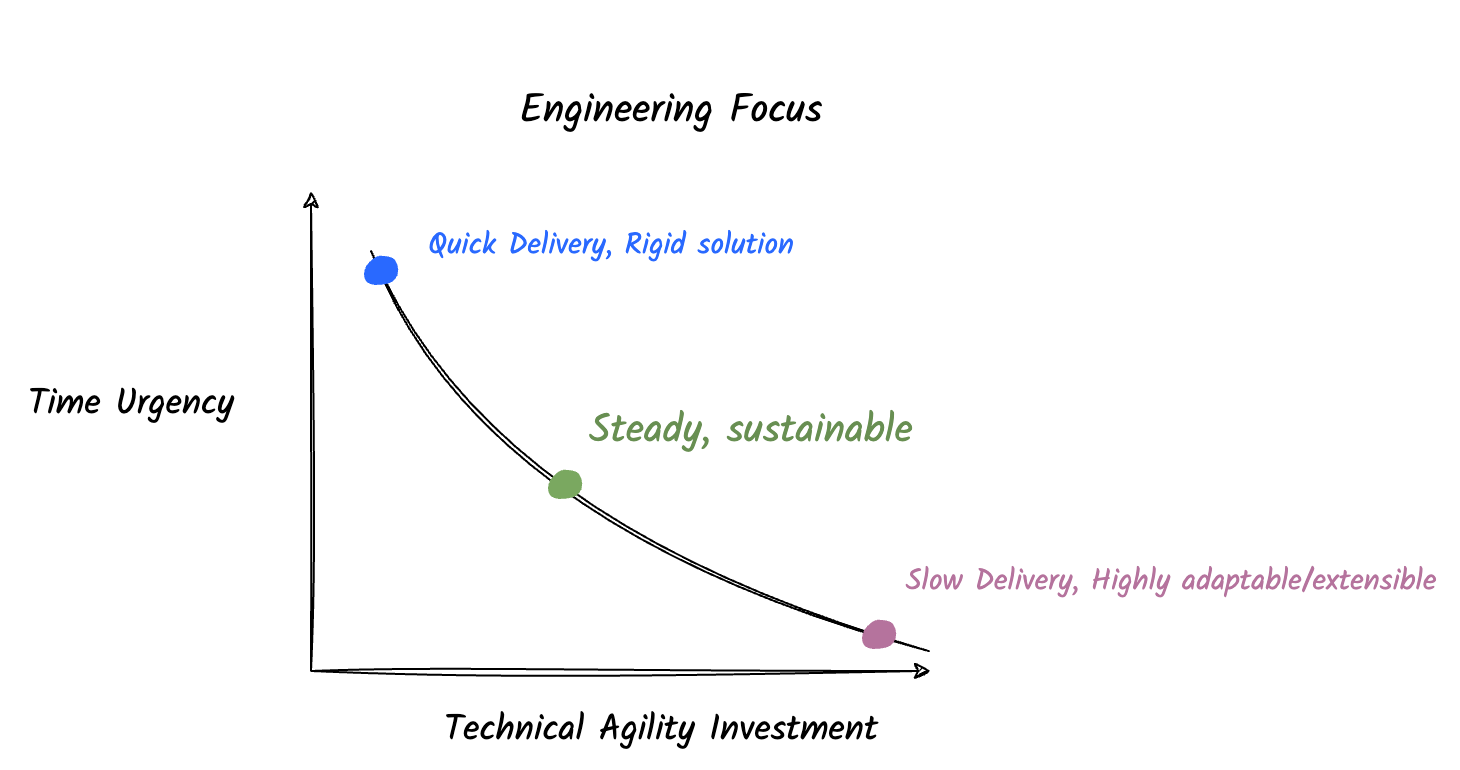

Is this enough to get us started? How quickly should we deliver? How much should we invest in technical agility at a specific time?

On top of these questions, there is a fine line between adequate and too much time investment and an over-engineered and under-engineered solution.

- How can we decide if you need to invest more or less time in technical agility vs delivery time?

The answer is simple but not easy to find. It all depends on the focus, what we want to optimize for at a given time which can change depending on the situation.

Defining the focus is the foundational step and affects every single decision we’ll make. Finding what you are optimizing for is a global requirement applied at all levels, from a company to teams and individuals. In this case, we see the engineering focus as a second-level dimension that runs parallel with OKRs and product direction.

When a company runs out of money if feature X is not delivered by date Y, delivery time is much more critical than technical agility. It’s necessary to have a correct rigid solution that does what it is supposed to do and invest more time later to fix it and make it more adaptable/extensible.

In other situations, we need the opposite; invest time in adaptability by compromising on the delivery time. For example, we might know for sure that in the next month, we have a new big feature coming up that cannot be supported easily by our current codebase. In that case, as part of the current cycle, we’ll dedicate more time to making our software more extensible, even if it’s not needed for our immediate requirements.

In general, the desired focus for a long-term sustainable way of working is a fast, steady pace that consistently delivers successful results on time.

2. Concentrate on what you know now. Don’t think too far ahead

Data and product assumptions are what drive us.

It’s very common for us engineers to overcomplicate things just because something is a future possibility.

We are common victims of the “neglect of probability cognitive bias” 2. Just because something is possible doesn’t mean it’s highly probable.

We need to focus on the requirements we’ve been given from business/product only. If something needs to be added, we can ask, of course. But if something is not required, don’t do it.

3. Enforce a non-negotiable Quality Baseline

At the very least, we should have a non-negotiable quality baseline for the software we deliver.

This quality baseline is what allows us to change the system’s behavior if needed or will allow us to build on top of it without restrictive limitations.

This is a non-negotiable baseline that is pressure agnostic. We need this quality baseline no matter how time-tight deadlines are with timelines.

Without it, things can get chaotic and quickly end up in an unrecoverable situation of a codebase that does not do what it is supposed to do; it’s challenging to troubleshoot and is very rigid in supporting new features.

The challenge with this baseline is that it is tough to determine how high or low it should be.

- So, How do you define the quality baseline?

There’s no straightforward answer to this. The quality baseline is often defined incrementally as we learn more about what works and what doesn’t. It’s very similar to the Definition of Done3 with a focus on the technical properties of the software.

A general rule of thumb is to opt for correctness first and then for maintainability in terms of readability, low-coupling, and high-cohesion, testing.

Advanced extensibility patterns and performance should only be considered if a considerable amount of data supports the need for it.

4. Keep it simple

“Keep it simple” is the most cliche guideline, yet one of the most common issues in software engineering teams.

This is not only a software engineering problem; it’s a human problem. We tend to think that complicated solutions can be better than simple solutions. This is commonly referred to as the complexity bias 4.

In software engineering, it has many forms and is disguised and infiltrates teams without being recognized until much later in the process. Some of its forms:

- The new shiny promising technology

- The induction of new technologies to solve a particular problem comes with overhead. Time overhead and one of the most underrated types of overhead: cognitive overhead. Do we really need it? Does it make our life easier or harder?

- The clever complicated solution

- “Clever systems produce clever problems”5. This statement can be significantly abused and should be used with caution. Finding the balance between when you need a complicated solution and a very simple one that does the work is not straightforward; it comes with experience.

The most significant advantage of keeping things simple is reducing the cognitive load of the team, which in fast-paced environments with continuously changing factors is crucial.

5. Embrace correct, quick, sub-optimal solutions where needed

While you navigate in this space of decision-making and while execution is what you are optimizing for, you’ll make decisions that are not optimal from a quality perspective. It’s fine.

We, engineers, appreciate our craft, and more often than not, we want to make all tasks “perfect”.

Perfect is entirely unattainable in software since there is always a tradeoff. Sometimes in the tradeoff equation, we have to inject the product time-to-market needs, not only technical data points.

Performance optimizations is a topic that is commonly talked about, however, this applies to every technical approach in the project.

Sometimes it’s ok to have something working correctly with a small negative effect if it does the job and the investment to fix the effect is significant. That’s exactly what tech debt is about, and if used correctly, it can be a great tool in your belt for success.

6. Carefully track tech debt and compromises

As we make sub-optimal decisions, we generate technical debt.

As seen in the previous section, this is accepted and is ok. However, tracking the optimizations/problems to be solved at the first opportunity is very important.

If you don’t, tech debt will come back and bite you.

If you are aware of the problems and have described them with enough context, you can negotiate time for it in the next loop and do it.

7. Move fast through two-way doors

We need to be as fast as possible with our decision-making. This is a global truth but is paramount, especially when we run against time.

One of the mental frameworks that can help us is the two-way doors vs one-way doors popularized by Amazon.6

- X seems like a good option, but I’m not sure if it will affect our future plans

- Can we change/roll back X quickly if needed?

- Yes

- 👉 Do X now and move on”

If it’s an easily reversible decision, don’t overthink it.

Do it and come back to it later if needed.

Is it a non-reversible decision? Take your time.

8. Use time-boxing to avoid analysis paralysis, accept mistakes

It’s almost certain that while working on a fast-paced project, we don’t have enough data to support a decision for moving forward. In such a scenario, we need to avoid the analysis-paralysis state.

“More is lost by indecision than wrong decision. Indecision is the thief of opportunity. It will steal you blind.” Marcus Tullius Cicero

There are two things that I keep in mind and help me cope with this:

-

Understand and accept that mistakes will happen

-

Time-boxed decisions. If it takes too long to decide, move forward with an approach and commit.

Accepting that mistakes will inevitably happen is very liberating. No matter how prepared you are, mistakes will undoubtedly occur in an environment with so much uncertainty and pressure for quick decision-making.

Even if you are cautious and have the proper framework for making educated decisions, some things are out of your control. Experience gives you a better perspective, and using your failures to improve makes us better in decision-making. Accept the facts as they are, and avoid repeating the same mistakes.

Conclusion

Decision-making in a product-driven environment with time-sensitive milestones and deadlines is tricky and challenging. Everything is based on limited knowledge and only assumptions.

To thrive in these environments, we need a focus, and depending on what we are optimizing for, we need to strive for technical agility while balancing delivery time.

Mistakes will inevitably happen, but we can minimize them by following a pragmatic, systematic approach to decision-making. The less we have to think, the more efficient we can be.

I hope the above guidelines set a framework that enables speeding up decision-making and balancing technical quality with delivery speed in a pragmatic fashion.

Leave a comment