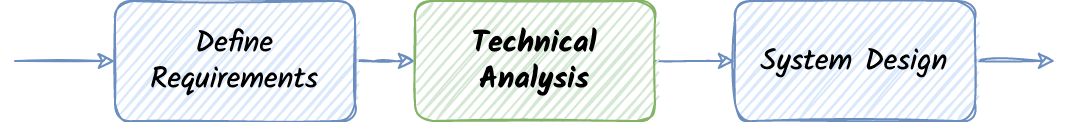

A systematic approach to Technical Requirement Analysis

This article describes a methodical way of approaching Technical Requirement Analysis that includes a list of steps that help in clarifying ambiguity and preventing unexpected issues before an engineering team jumps into the design phase.

Introduction

There is an astounding amount of literature on approaching different Software Development LifeCycle (SDLC) frameworks that provide the steps, practices, and guidelines required to achieve an efficient software development process. A typical, generic SDLC consists of the following stages:

- Requirement Gathering

- Analysis

- Design

- Implementation

- Testing

- Delivery

Most times, software engineers are involved in this whole process after the business requirements analysis and definition phase with the responsibility to design, implement, test and deploy applications.

Between the handover of the requirements from the product team to the engineering team and the initiation of the design phase, there is a short period in which engineers work with the product team to clarify any ambiguous requirements, talk about potential issues, and agree on specific business specs. This phase is under the Analysis stage and in this article, I refer to it as Technical Requirement Analysis.

In my view, the Technical Requirement Analysis is one of the most critical phases in the lifecycle. Unfortunately, in my experience, it is one of the phases that is often rushed and sometimes even overlooked. However, if done right, it can catch issues early in the process, saving future time and money.

During the last years, I have been involved in analyzing and designing quite a few projects and features. However, finding a perfect solution to approaching the Technical Requirement Analysis is very difficult, if not impossible; Different companies, teams, people use different tools and methods to complete the technical analysis.

Recently, I have tried to document the way I approach Technical Analysis in a structured manner that I can use as a template for the technical analysis of future features. Personally, I find that following a methodical approach with a set of recommended steps can prevent consistent errors and provide the necessary confidence to proceed to the design phase. This need for a systematic approach is the motivation behind this article.

In the following sections, we will explore the importance and how we can benefit from a detailed Technical Analysis phase and provide a set of well-defined, structured steps to minimize unclarity and future inconvenience.

Importance

Many teams see the technical analysis as a quick phase to read through the requirement definition and clarify a few ambiguous statements.

However, a team can significantly benefit by following a few extra steps before the design phase. The goal of an SDLC is efficiency; while iterations help immensely in this aspect, catching potential issues in the technical analysis phase can further increase efficiency by preventing delays from edge-case scenarios and the collateral impact that affect the requirements.

The Technical Analysis of Requirements phase is critical for many reasons:

- It ensures that engineering and product are aligned on the goal and the problem this feature is trying to solve. While the product team gathers the requirements from the stakeholders and is aligned with the business, it is also essential that the engineering clearly understands the defined requirements. This alignment will ensure that the end goal is the same from all teams’ perspectives.

- It allows engineers to raise concerns and present possible issues on the requirements. Firstly, some features can be technically infeasible. This is usually prevented by having a technical presence when the product defines the business requirements. However, even for feasible issues, the technical team might raise risks and present technical challenges that are not trivial to catch at the requirement gathering phase.

- It allows engineers to give their input and perhaps reshape the requirements. While the product/business team sees the requirements from a customer perspective, engineers can identify collateral, technical consequences, future codebase quality issues that should be considered. Depending on the priorities and the long-term vision, this input from engineers might change the course of the feature and alter some of the requirements. A minor tweak that is not so important for the product can decrease the complexity and consequently the delivery time of the feature.

A simple, methodical Technical Requirement Analysis approach

As also mentioned in the introduction, in my experience working on new features, I have not seen a standard way to approach Technical Analysis. However, through the years and my interaction with fellow engineers, I have personally used a few tools, and I have been incrementally optimizing my approach on this.

In this section, I will be sharing this approach.

Of course, this is by no means a phase that has to be strictly defined and may not be applicable for all use-cases, but I believe some of the steps can be helpful.

1. Read the docs!

Quite obvious, uh? Well, yes, it is :)

Image generated by gopherkon

This first step begins with handing over the requirement definition from the product to the engineering.

The technical requirement analysis should ideally be a team activity. The engineering team should dedicate enough time to read the requirements and ensure that all members understand what is the problem, why it needs to be addressed, and how the feature requirements handle it.

If there are any unknowns or missing context, this is the time to ask questions about the product and seek a complete understanding of the requirements.

Additionally, reading and clarifying requirements brings the added benefit of expanding engineers’ domain knowledge and makes the engineers feel more engaged.

2. Edge-Case Analysis - Business Specifications

Once the requirements are well understood, the team should proceed with the in-depth edge-case analysis stage.

Image by Maria Letta @free-gophers-pack

Often, the requirements presented from the Product cover the essentials and potential business-related side-effects, but the engineering perspective can bring edge cases that are related to the system behavior and impact on other services that the product might be unaware of.

The purpose of this step is to raise these edge cases, and if it’s possible, to present available options to manage them and even propose a recommended way forward. The edge-case analysis step consists of 3 substeps: a. Identify Edge Cases b. List Edge Case Resolution Options c. Present recommendations (For technical-impacting features)

a. Identify Edge Cases

The team should look at the requirements with the engineering lens and understand any technical edge cases in the requirements.

Let’s look at an over-simplified and open-ended example(usually, requirements are defined in fine detail).

Example: We may have a requirement from the product to ‘send an email to a user when their account balance changes’. Then, the engineering team can bring the edge case of ‘‘What happens when the email provider is not available at the time of the change?’ or ‘How do we deal with bounced back emails?’. Almost all requirements have such edge-cases. Capturing them in this stage is vital for smooth progress to the following stages.

b. Document Edge Case Options

Once the edge cases are identified, the team can prepare a list of options with pros and cons. This is the step that is often skipped, although it is such a useful activity with three crucial benefits:

- Documenting the options further enforces the team to think deeply about possible options. Casual discussions and brainstorming works fine, but documenting options is even better

- Options are the core of the analysis. The documented alternatives will serve as a valuable archive if/when we need to look back into why a decision was made

- If external input is needed, documented options are necessary and provide a good baseline for asynchronously exchanging views.

This step is about finding and documenting options, not making decisions; Decisions will be taken in the next step.

Example: From the previous example, ‘Send an email to a user when their account balance changes. What happens when the email provider is not available - our email provider SLAs are 99% availability’ the options could be:

- Option 1: Send the email when the provider is available

- Pros:

- From a channel perspective, the requirement is met, the customer will eventually receive the email

- Cons:

- Technically complicated. Requires retrial policy management that is currently not available

- Follow-up questions:

- How quickly should we retry? Do we have a maximum time window for retrials?

- Does our provider’s SLAs meet our requirements?

- Pros:

- Option 2: Fallback to SMS

- Pros:

- Immediate response, good customer experience.

- Cons:

- This might fail too

- The customer might not have a mobile number

- Pros:

- Option 3: Don’t send an email automatically. Track errors and send them manually

- This is not an option since it doesn’t cover the automated requirement

- Pros:

- Technically Easy

- Cons:

- If this is a marketing promotional email, it may be ok. But if this is a financial status-related email, it wouldn’t be acceptable.

c. Edge case resolution - Recommended Approach

Suppose the requirement is purely technical, and the technical complexity between solutions varies with impact on different metrics such as delivery timelines, introduced tech debt, troubleshooting convenience, etc.

In that case, the engineering team can propose a recommended approach. This will help drive the edge case resolution more quickly if the product agrees.

3. Finalize revised Business Specs

Once the requirement clarifications are given with all edge cases documented with possible options and the recommended approach, the product team can review the new information with the engineering team and present it to the stakeholders.

In this phase, the product team must understand the edge cases, the concerns from the engineering side, and based on that, make informed decisions taking into account the pros and cons of the selected approach on how to move forward.

4. Data Flow Analysis

Having well-defined requirements with all edge cases, the engineering team can proceed with the technical data flow analysis.

Image by Maria Letta @free-gophers-pack

This step is often grouped under the technical design stage. Still, I find that doing this at a high level earlier in the process offers excellent initial feedback on the data requirements of the requested feature.

I like to think of the feature in question in terms of input and output in this stage. All features require input and produce output, which can be the base of this phase.

Based on the input requirements, the team needs to identify a. If the input is already available - For example, will the input provided by the client or already exists within an internal component b. If it is not available, determine where the information is - For example, if the input required is missing, determine which external sources are the owners of the data we are looking for.

The output should reflect the requirements as well. For example, if the output is a data object, then an initial version of the schema can be defined in this stage. This schema definition is handy when working on features for which the output is a blocker to another feature implemented by an external team.

Since this is still the analysis stage, we shouldn’t expect a finalized schema/model for input and output but an indicative set of data points that should be considered for design purposes.

5. Extract Use Cases

The next step is to identify the use cases.

We can think of use cases as individual operations that should be served by the application to meet the requirements.

A helpful tool we can use in this phase is thinking of use-cases in terms of Commands and Queries. If a requirement refers to an operation that provides data, it can be considered a ‘Query’. On the other hand, if the operation modifies data, it can be regarded as a ‘Command’. This separation of use-cases is particularly useful when working with codebases using Clean Architecture.

At the end of this step, the engineering team should have a clear picture of the requirements in very great detail, and they can start visualizing how the technical design would look.

TL;DR; Overview

Here is an overview of the Technical Requirement Analysis Steps

| Step | Goal | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | Read the docs | Understand what, why, and how | Requirements are clear |

| #2 | Edge-case analysis | 1. Identify technical edge cases 2. Present possible options to deal with technical edge cases 3. Propose recommended approach |

Documented edge cases with options and approach |

| #3 | Finalize business specs | Based on the edge case analysis, finalize business specs | Documented final business specs |

| #4 | Data flow analysis | Identify required data Find required input data Define output data | Input Data Requirements with their owners Defined output model/schema |

| #5 | Extract Use Cases | Defind the use-cases of the requested feature | Documented use-cases in commands and queries |

You can also find a very simple template in markdown here

Conclusion

That’s all. We have gone through a structured approach that I have been following during the last years. I have seen it producing excellent results regarding common expectations/alignment between product and engineering and stakeholders in general and preventing delayed capturing of edge cases.

This is a process, and naturally, some of its steps might be applicable in one context but not in another. However, I find structure in this phase very beneficial as it gives a sense of progress and a set of objectives to look for before proceeding with the design.

Leave a comment