Outbox pattern - Why, How and Implementation Challenges

This article presents the outbox pattern, a communication/messaging pattern used in event-driven distributed systems that allows executing database operations and reliably publishing messages.

We will examine why we need the outbox pattern, how it works, and its implementation challenges.

Introduction

In the distributed services world, services communicate with each other synchronously and/or asynchronously. Synchronous communication is most commonly achieved through HTTP or gRPC calls. Asynchronous communication is achieved through the exchange of events via a message broker.

Modern, event-driven architectures use asynchronous communication for intercommunication purposes, based on the fact that its nature can provide numerous benefits, including more straightforward scalability, high decoupling, and fast processing time. However, this asynchronous nature introduces multiple challenges that we need to resolve to ensure a robust system.

One of these challenges in event-driven architecture is the guaranteed message delivery after completing a database operation. We cannot be sure that when we need to deliver a message, the message broker will be available to receive the message. In some cases, it is essential to guarantee the message delivery along with local operations to support the requirements of a system.

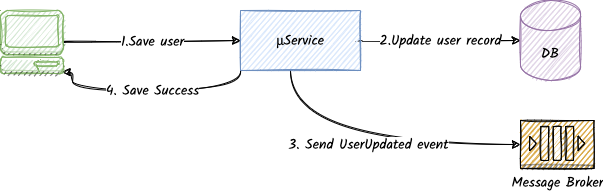

Let’s look at an example of a typical scenario in a microservice:

- The service receives an entity-related request via an HTTP API

- The handler processes the request and stores the updated entity in a persistent storage

- Then, it publishes an event containing the latest snapshot of the entity

- If the storage and the event/command publishing is successful, return a successful response

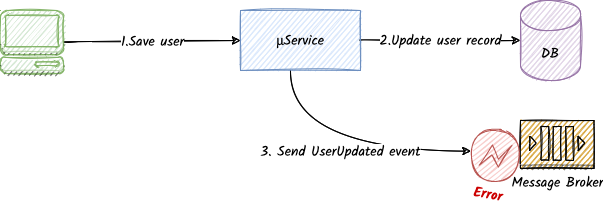

- Q: What happens if the message broker is not available at the time of the message delivery

- A: We can rollback the change we just applied on the database.

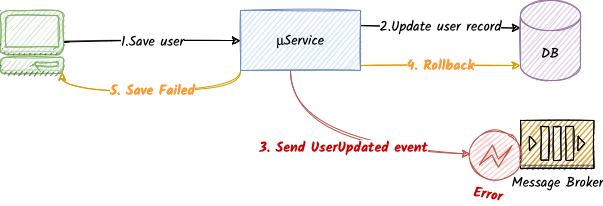

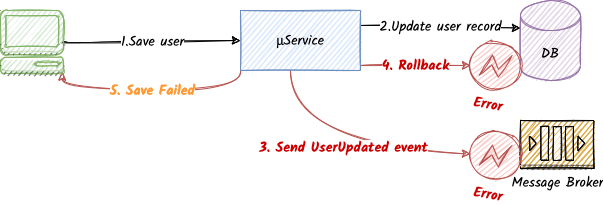

- Q: But what if the database is not available at that time? Or what if the program somehow crashes?

- A: Well, we end up in an inconsistent state. The database will have the entity changes stored, while the external subscribers will never get notified.

How do we resolve this?

The database operation and the message publishing have to be done in an atomic fashion. And this is where the outbox pattern comes to save us!

The outbox pattern

The outbox pattern achieves atomicity in scenarios where we need to perform operations in persistent storage and then publish a message. It does this in a single atomic operation by taking advantage of RDBMS transactions.

How does it work?

The outbox pattern consists of two main components

- The

outboxdatabase table This table is located in the local database that holds the outbound messages to be sent. - The

message dispatcherThe message dispatcher is a background worker that observes and publishes the entries of theoutboxtable to the designated message broker

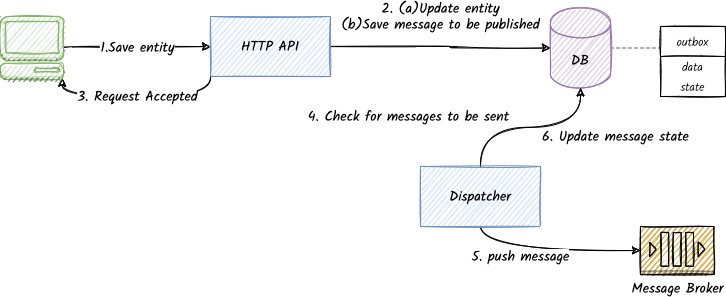

Request Handler:

- The service receives a request

- The request handler prepares and commits the business database operations and the message publishing operation in a single atomic database transaction. As part of this atomic transaction, the message to be delivered is stored in the

outboxtable- If the transaction fails at this point, we notify the client that something went wrong. No harm here; neither the business database operations are stored, nor the message is published.

- The request handler returns a response indicating that the request is accepted

Dispatcher:

- In the background, in a separate instance, the

message dispatcherobserves the entries in the database - If a new message is found, the dispatcher delivers the required messages to the message broker

- If the delivery is successful, it marks the message as delivered.

- If the message delivery operation is not successful, the dispatcher will retry later following a retrial policy

The outbox pattern guarantees at least once delivery. The dispatcher can send duplicate messages because we can still fail after the message broker delivery when the dispatcher tries to update the database record.

While this is a general best practice, especially when using the outbox pattern, consumers should be idempotent1. They should expect that they may receive the same message and should handle this without any issues.

That’s it. Very simple but very powerful at the same time. Let’s explore the implementation details in the next section.

Implementation

While the outbox pattern is simple as a concept, its implementation can become considerably complicated. Depending on the system’s requirements using outbox pattern, we have some mandatory and some optional requirements.

Mandatory Requirements

- Retrial policy

- The primary purpose of the outbox pattern is to ensure message delivery reliability. While the database transaction guarantees atomicity, we also need to ensure that the message is delivered successfully even if the message broker is unavailable for some time.

- A typical retrial policy will include

- Time between attempts (how much time should the dispatcher wait between attempts?)

- If discarding a message is an acceptable action for messages that are retried many times or for too long

- Maximum number of attempts (how many times should the dispatcher attempt to deliver the message before it gives up?).

- Maximum total duration of retrials (from the time that we received the message request, how long does it make sense to retry sending the message)

- Retention policy

- Messages are stored for reliability purposes, not for auditing purposes. For this reason, we need to ensure that we don’t leave the outbox table expanding forever and never delete any records

- A typical retention policy includes a time duration threshold to keep the records in the database

Optional Requirement

- Order of messages

- While a strict order of message delivery might be required in some cases, some systems do not have this requirement

- If maintaining the order of the messages is not needed, we can be parallelize the solution to reduce the delivery time by delivering multiple messages at the same time

In the following subsections, we explore the implementation components of the outbox pattern and explain the challenges and approaches that we can follow depending on the requirements.

The outbox table schema

The outbox table, based on the above requirements, needs to hold:

| Column | Description |

|---|---|

Message Data |

The contents of the message to be sent |

State |

The current state of the message: Processed, Unprocessed, Discarded |

Error Description |

Contains the last attempt’s error. This can be expanded to contain a series of errors per attempt |

Delivery/Discard Datetime |

The datetime that the message was delivered/discarded |

Creation Datetime |

The time the record was created |

Message to be sent

This column is mostly straightforward; it holds the data we need to send to the message broker.

The important thing to note here is that since the message to be sent can hold any type of data, the data should be serialized/encoded in a predefined way known to the message dispatcher.

Depending on how generic we want the outbox implementation to be, we could introduce different encoding types that we can represent with an additional column that we can name encoding_type. The only prerequisite is that the dispatcher should support decoding the message data.

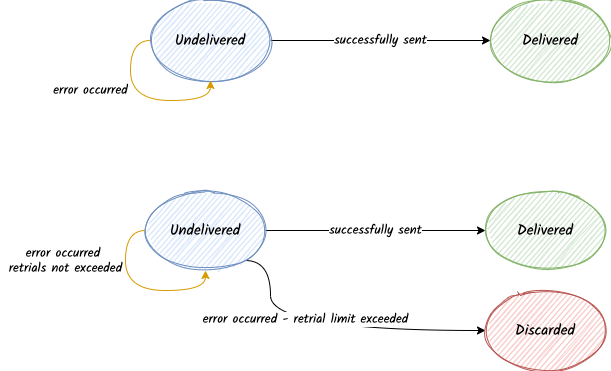

State

The state column is used to control the flow of the message.

Every message starts in the Undelivered state, and it proceeds to the Delivered state when it is delivered successfully.

It can also end up in a Discarded state if the message is discarded. This scenario can occur when the dispatcher has tried to send the message multiple times, exceeding the maximum retrials threshold.

Retrial Policy

The number of attempts column is required to ensure that we have not exceeded the maximum retrial threshold.

Likewise, the last attempt time column is required to ensure that the maximum attempt duration is not exceeded either.

Delivery/Discard Time

This column is required for retention purposes. As the number of messages to be sent grows, we need to apply a retention policy based on time. Using this column, we can, for example, periodically archive or delete the ‘completed’ entries older than X hours/days/weeks/months.

Storing Messages to the Outbox Table

The most straightforward part of the outbox pattern implementation is storing messages to be sent within the outbox table.

We have two main approaches that an implementation can follow:

- Allow applications that use the pattern to directly write to the outbox table by following the guidelines of the schema

- Requires knowledge of the dispatcher implementation and probably the message broker technology to know how to encode the data

- Can be heavily customized to the requirements of the RDBMS and Message Broker capabilities that can increase efficiency

- Provide an SDK utility, an outbox storage service that accepts the data and the database transaction information and manages the storage of a predefined behind the scenes

- Can handle encoding and provide a generic message data model that can be applied for any RDBMS and Message Broker Technology

- Can be less efficient because of its generic nature

For both of these approaches, we can use the Unit of Work(UoW)2 pattern. The UoW will ensure that both business operations and the outbox pattern will be committed as a single unit.

Dispatcher Implementation

The message dispatcher is the heart of the outbox pattern. The dispatcher is responsible to

- Observe the outbox table for new messages

- Manage the outbox records lifecycle

- Deliver the messages to the message broker

- Handle errors

- Apply the message retrial policy

Let’s examine each of these steps in more detail.

Message Observation

The message dispatcher has two main ways to ‘observe’ new messages:

- Polling

- Periodically query the

outboxtable to findUndeliveredmessages - Applicable for any database

- Periodically query the

- Transaction log tailing

- Continuously monitor the database transaction log for new

outboxtable entries and directly trigger the processing once an entry appears - Only applicable for databases that provide an interface to monitor transaction logs such as MySQL and Postgres

- Requires extra complexity for implementing a retrial policy

- Continuously monitor the database transaction log for new

Dispatcher Flow/Algorithm

The flow follows the steps below:

- The service, as part of the transaction, stores the encoded message to be sent in the outbox table in an

Undeliveredstate - A single instance of the dispatcher periodically checks for new entries by querying the

outboxtable forUndeliveredentities that meet the retrial policy rules - For all unprocessed entries

- Decode the message

- Send the message to the message broker

- Increase the number of attempts, update the last attempt datetime and update the state

- If the sending was successful, mark the message as

Delivered - If it failed leave it as

Undelivered

- If the sending was successful, mark the message as

Message broker specific or generic

Different message brokers might have other message data requirements which should be considered when designing an outbox implementation.

Fortunately, most of them have typical requirements such as a message key, payload,and headers, and that’s it. However, suppose we need more advanced features per message broker while also supporting multiple message broker providers. In that case we need to provide an extensibility mechanism and the foundation for this to be supported. A generic Message interface that can be broker-specific can do the job here.

Error handling

While the main algorithm section provides a generic description of the flow, it is not bulletproof. We have dependencies on the database provider and the message broker that are external services we need to account for possible failures.

- When the order of messages is not required, if a message delivery fails due to message broker unavailability and I have more in the queue, should I try to process them?

- Probably not. We need to track errors and try later depending on the error type (i.e., network).

- If I try to save the updated state to the database and it is not reachable, how can I proceed?

- A solution would be to sleep for some brief duration and retry. The database is a crucial component to manage the state, and therefore it doesn’t make sense to proceed with other records if the database is not reachable.

- What happens with a discarded message that exceeds retrial times?

- The dispatcher has tried to send a message X times and failed. So it has discarded the message. Should we notify someone about these types of messages to take a closer look?

These are not uncommon scenarios, and it is crucial to determine how our implementation deals with them in each case.

Coordinating Multiple Dispatcher Instances

High availability is a requirement in distributed systems, and this applies to the dispatcher too. While the above algorithm describes an environment where a single instance of a background worker is only running, depending on the infrastructure, it is possible to have multiple instances running at the same time.

Having parallel dispatchers introduces a couple of problems that we need to address:

- Maintain the order of events if needed

- Avoid sending multiple identical messages from different dispatchers

We have typical distributed system consensus challenges in an environment that manages multiple instances of an outbox dispatcher. We should only allow one instance of a worker to process/deliver an outbox record.

In these types of scenarios, we have two ways we can approach these:

1. Multiple instances deliver concurrently different records

- This approach does not maintain the order of messages, which can be a mandatory requirement depending on the use case

- With this approach, we need a locking mechanism in place

- An instance of a dispatcher locks the messages that it will process

- If the lock was successful, then proceed with the delivery

- Once finished, unlock the record

- The problem of locking can get quite complex when handling error scenarios, for example, when an instance fails to unlock the message.

- Mechanisms need to be introduced to unlock stale messages periodically

2. Only one instance - the leader - processes and delivers messages

- Guarantees the order of messages

- Requires a consensus stage in which all instances elect a leader3

- Can be complicated to implement

Retention Worker

In addition to the dispatcher, we also need a retention worker running periodically responsible for deleting/archiving events older than X months. The retention operation can be part of the dispatcher’s algorithm, or we could use a cronjob executed periodically every x days.

Conclusion

We have seen the outbox pattern, an instrumental pattern found in event-driven systems. As we have seen in this article, it ensures message delivery reliability when we need to execute database operations and message delivery as a unit and commit them atomically.

While simple as a concept, it can be complicated to design and implement as there are a lot of edge cases and decisions to make that affect its performance and extensibility.

For an implementation of the outbox pattern in go you can check my blog post here.

Leave a comment