Clean Architecture in Go [2024 Updated]

❇️ This post and the respective repository was updated in August 2024 to reflect a simplified infra layering approach and more accurate terminology

This article covers the fundamentals of the Clean Architecture design concept and demonstrates how to apply its principles in Go through a simple web app implementation.

Introduction

The one constant in software development is change.1

Change in software development introduces risk. The risk occurs since modifying working code can introduce bugs. Besides bugs, without a solid design approach, your codebase will quickly become a mess.

As software engineers, we reduce this risk by applying architecture and design patterns that promote decoupling and separation of concerns2; Keeping areas of a codebase that change more frequently or serve different purposes separate.

Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob) introduced Clean Architecture almost a decade ago3 to tackle the risk of change. Since then, it’s been one of the go-to architecture design concepts for building modern enterprise applications.

Clean Architecture Fundamentals

Clean Architecture is a software design concept that isolates change through the separation of concerns. Its primary focus is separating business logic from the infrastructure of an application. It does this by dividing software into layers.

The separation of software in Clean Architecture is based on the purpose and dependencies of the software components.

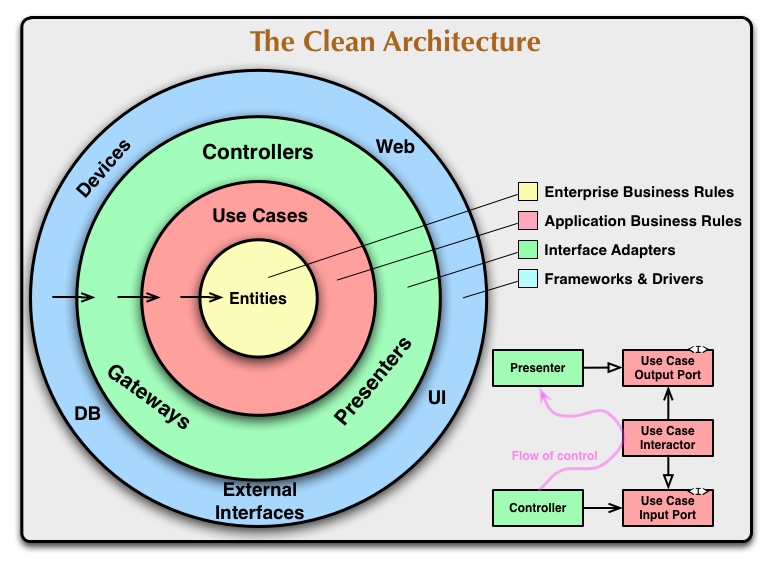

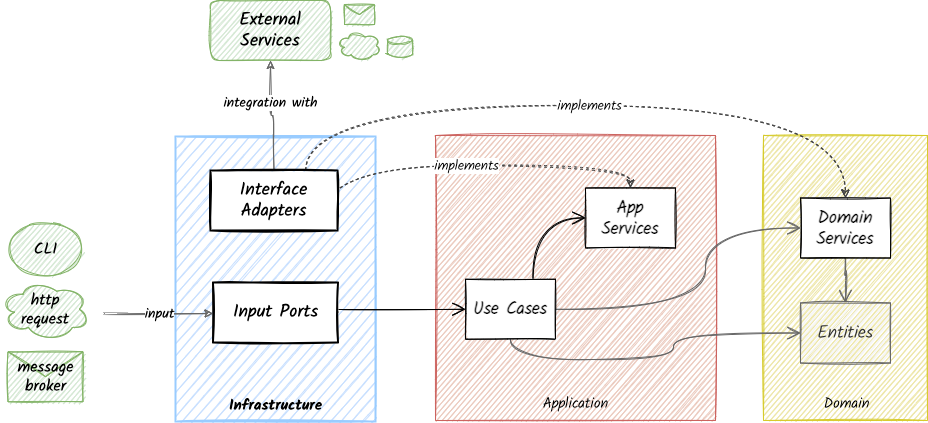

The above diagram is from the original post by Uncle Bob3. Circles contain different software components based on their purpose/concern. The rule of this diagram is that outer circles always have to depend on inner circles.

In combination with Domain Driver Design concepts, these four circles are often grouped into three main layers:

- Domain → Enterprise business rules

- Application → Application use cases & business rules

- Infrastructure → Interface adapters + Framework & Drivers

- It is common to merge these two outer circles into one since both depend on application and domain - they don’t have any inter-dependencies

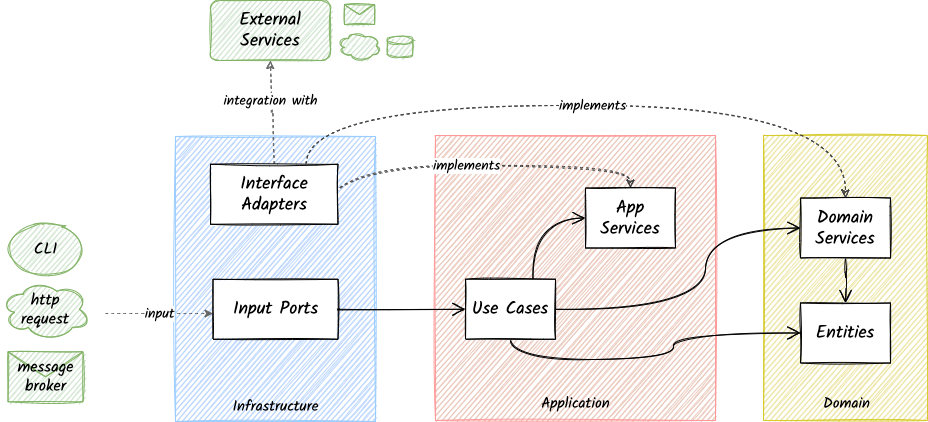

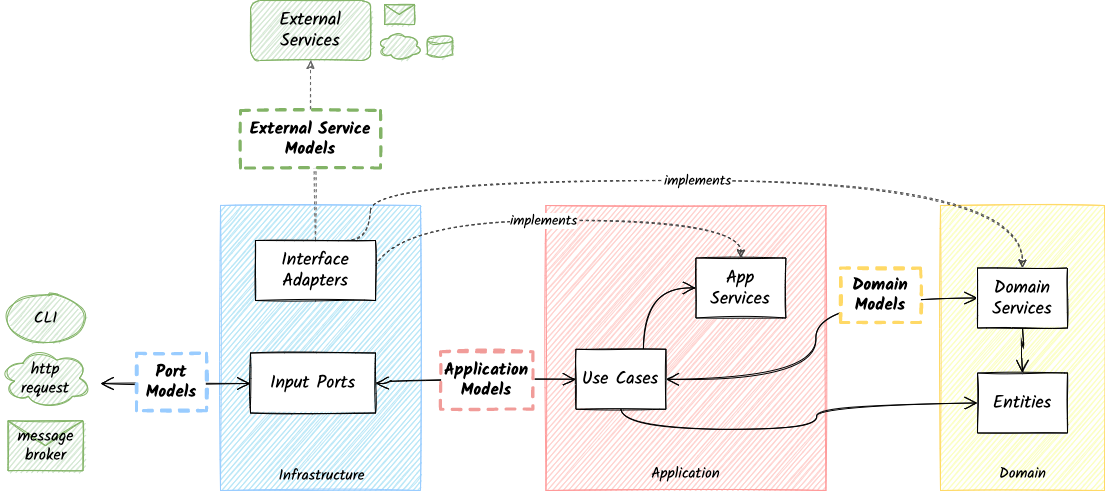

Here is an alternative diagram containing the main components of an application that matches the three-layer grouping.

We will describe these three layers in detail in this article. The main idea is the same as in the original diagram. Each layer has well-defined boundaries and dependency rules, represented by the arrows and their direction.

Let’s explore each of these layers in more detail.

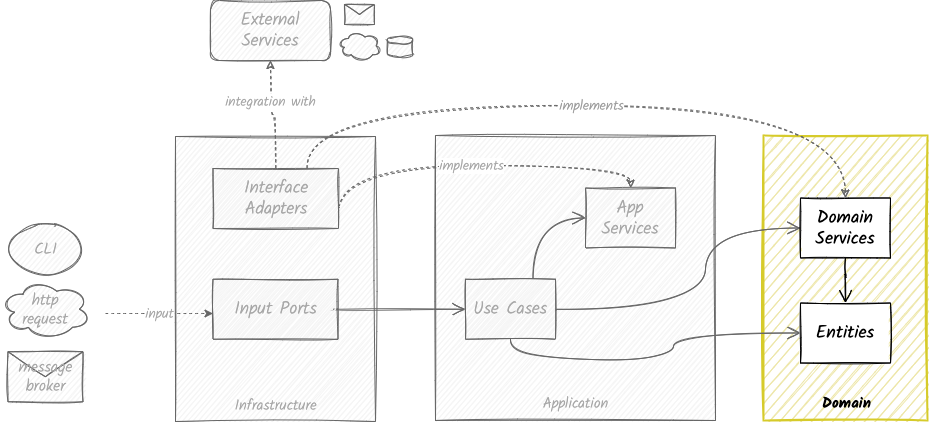

Domain

The domain layer contains the components of the application that describe the business foundations:

- Domain Entities & Value Objects

- You can think of these as the data structures of the business domain

- Entities are uniquely identifiable structs

- Value Objects are structs that are identifiable by their properties, and they describe the characteristics of an Object.

- Domain Services

- They provide domain functionality using entities and objects

- i.e., data repository

- They provide domain functionality using entities and objects

Domain Dependencies

The domain layer does not have any dependencies on other layers. It is also only used by the application layer (This is not strictly always applied; more on that later in data contracts)

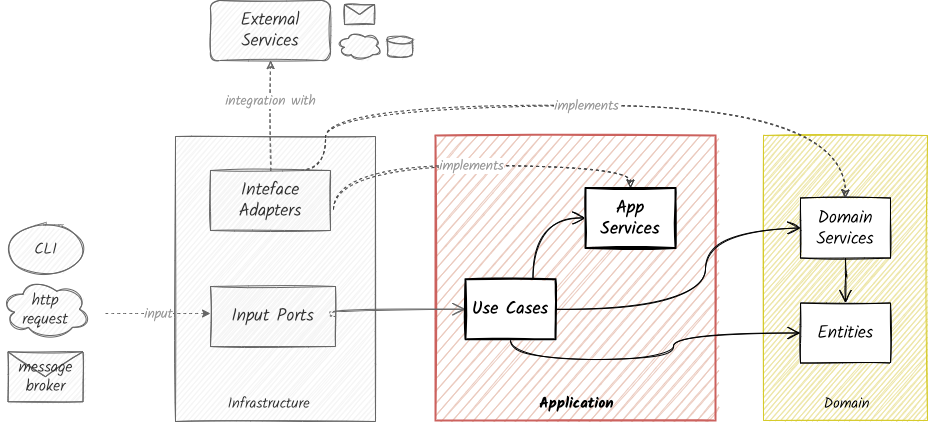

Application

The application layer exposes all supported use cases of the application to the outside world. It consists of:

- Business logic/Use Cases

- Implementation of business requirements

- We can implement this with command/query separation. We cover this in our sample application.

- Application Services

- They provide isolated business logic/use cases functionality that is required. This functionality, is expressed by use cases.

- It can be an interface-only service if it is infrastructure-dependent

Application Dependencies

The application layer code depends only on the domain layer.

Infrastructure

Typically, software applications have the following behavior:

- Receive a signal/input to initiate an operation

- Interact with infrastructure services to complete a function or produce output.

For the entry points from which we receive information (i.e., requests) I use the term inbound communication handlers. For the gateways through which we integrate with external services I use the term interface providers.

Inbound communication handlers and interface providers depend on frameworks/platforms and external services that are not part of the business or domain logic. For this reason, they belong to this separate layer named infrastructure. This layer is sometimes referred to as Ports & Adapters.

Interface Providers

The interface providers are responsible for implementing domain and application services(interfaces) by integrating with specific frameworks/providers.

For example, we can use a SQL provider to implement a domain repository or integrate with an email/SMS provider to implement a Notification service.

Inbound communication handlers

The inbound communication handlers provide the entry points of the application that receive input from the outside world.

For example, an inbound communication handler could be an HTTP handler handling synchronous calls or a Kafka consumer handling asynchronous messages.

❇️ Update: In the initial version of this blog post, interface providers and inbound communication handlers were referred as interface adapters and input ports. This terminology can be confusing when thinking about these terms in the Ports and Adapters Architecture.

Infrastructure Dependencies

The infrastructure layer interacts with the application layer only. (again only is a strong word here; more on that below in data contracts)

* In applications that also present information (i.e., server-rendered web pages), this layer also contains the presenters; components responsible for returning compatible views to the clients

Clean Architecture applied in Go

Clean architecture is a design concept with guidelines; it does not dictate exactly how to implement an application.

For this reason, please take the following reference implementation as my adaptation of this concept in Go; not the only way to apply clean architecture.

Furthermore, please note that this example focuses on demonstrating clean architecture structure and dependencies. Therefore, essential practices on validation, error handling, and testing are not implemented for conciseness.

Go Climb Application Overview

What is Go Climb?

The sample application, Go Climb, is a climbing crag management web API. Its purpose is to manage a crag directory by providing simple CRUD operations.

The scope of this application is kept minimal for conciseness.

Where can I find the code?

The complete source code is here: GitHub repo.

Use Cases

Before we move to the implementation details, let’s see the use cases that this application implements. Use Cases will help us design the application logic of the application.

As a web client, I want to be able to

- Get all available crags.

- Get a crag by ID.

- Add a crag by providing a name, country, and description.

- Update a crag by providing a name, country, and description.

- Remove a crag by ID.

As an application administrator

- When a new crag is added, I want to receive a notification at a pre-agreed channel.

Technical requirements

- Operations should be exposed via an HTTP restful interface.

- For simplicity purposes,

- The crags should be stored in memory; no need for persistence storage.

- Notifications should be sent in a console application.

Project structure

How should I structure my Go application?

This is a common question and a well-discussed topic among gophers. The two main approaches used within Go projects are group-by-feature and group-by-type. The general consensus accepts the group-by-feature as the correct and more idiomatic approach between the two.

Group by type approach

In the group-by-type approach, code is structured so that files containing a specific type. Interfaces, for example, are grouped all together in a package named interfaces. This is a bad practice since code loses context, and troubleshooting and maintenance can become difficult. It also introduces spanning changes across many packages that increase the risk of introducing bugs.

Group by feature approach

In the group-by-feature approach, we can have different elements in the same package if they implement a single feature. So, for example, crag entities, repository, and crag-related use cases would belong to the same package crag in our sample application.

Clean Architecture - Group by layer approach

This article uses a different method to demonstrate clean architecture, the group-by-layer or group-by-concern approach. The group-by-layer approach adds an extra level on the top of the hierarchy to group components based on the layer they belong to. Each layer contains its isolated packages that follow the group-by-feature approach.

Group-by-layer is helpful for a couple of reasons:

- Clean architecture focuses heavily on the dependencies between layers. We can express this intuitively by defining boundaries between layers through structure.

- Having files grouped per layer/concern could also make the violation of dependencies harder.

- This layered structure can induce some ‘rules’ on importin packages between layers. This reduces uncertainty when adding new features.

Perfect, let’s check how the group-by-layer approach looks like in the Go Climb Source Code.

Go Climb Project Structure

Go Climb follows the group-by-layer structure:

├── go-climb

│ ├── cmd/

│ ├── docs/

│ ├── internal

│ ├── app

│ │ ├── crag

│ │ │ ├── commands

│ │ │ └── queries

│ │ ├── notification

│ │ │ ├── mock_notification.go

│ │ │ └── notification.go

│ │ ├── services.go

│ │ └── services_test.go

│ ├── domain

│ │ └── crag

│ │ ├── crag.go

│ │ ├── mock_repository.go

│ │ └── repository.go

│ ├── infra

│ │ ├── http

│ │ │ ├── crag

│ │ │ └── server.go

│ │ ├── notification

│ │ │ └── console

│ │ └── storage

│ │ ├── memory

│ │ └── mysql

| │ └── pkg

| │ ├── time/

| │ └── uuid/

│ │ └── sevices.go

│ └── vendor/

cmdcontains themain.gofile, the entry point of the applicationdocscontains documentation about the applicationinternalcontains the main implementation of our application. It consists of the three layers of clean architecture + shared utility code underpkg/- infra

- app

- domain

- pkg

Each of these directories contains its corresponding components, following the group-by-feature approach.

vendorcontains the dependencies of our project

Great, we know how the high-level project structure of Go Climb. Let’s explore the contents of each layer.

Domain

domain

└── crag

├── crag.go

├── mock_repository.go

└── repository.go

The domain of this application is straightforward, with one package crag. crag contains:

- One entity - the

crag.Crag//Crag Model that represents the Crag type Crag struct { ID uuid.UUID Name string Desc string Country string CreatedAt time.Time } - One domain service interface - the

crag.Repository// Repository Interface for crags type Repository interface { GetByID(id uuid.UUID) (*Crag, error) GetAll() ([]Crag, error) Add(crag Crag) error Update(crag Crag) error Delete(id uuid.UUID) error }- The

Repositoryis responsible for exposing data operations to the application layer - Since the repository depends on platform logic, its concrete implementation is delegated to the infrastructure layer

- The

MockRepositorycontains a mock implementation of theRepositoryinterface. This mock is needed for testing purposes.

- The

Dependencies/Interaction with other layers

The domain layer consists of pure domain code that does not have any external dependencies.

Application

├── app

│ ├── app.go

│ ├── app_test.go

│ ├── crag

│ │ ├── commands

│ │ │ ├── addcrag.go

│ │ │ ├── addcrag_test.go

│ │ │ ├── deletecrag.go

│ │ │ ├── deletecrag_test.go

│ │ │ ├── updatecrag.go

│ │ │ └── updatecrag_test.go

│ │ └── queries

│ │ ├── getallcrags.go

│ │ ├── getallcrags_test.go

│ │ ├── getcrag.go

│ │ └── getcrag_test.go

│ └── notification

│ ├── mock_notification.go

│ └── notification.go

The application layer contains the business logic of Go Climb, extracted from the business requirements.

Application Use Cases

Use cases are split in

- Queries; operations that request data

GetCragByIDGetAllCrags

- Commands; operations that accept data to make a change or trigger an action.

AddCragUpdateCragDeleteCrag

Each use case is defined by the following components (using ‘Get Crag By Id’ use case as an example):

- Command/Query Request input model; we can omit this if no input is required

//GetCragRequest Model of the Handler type GetCragRequest struct { CragID uuid.UUID } - Query/Command result model; this is mainly applicable for queries since commands don’t typically return information other than errors

// GetCragResult is the return model of Crag Query Handlers type GetCragResult struct { ID uuid.UUID Name string Desc string Country string CreatedAt time.Time } - Command/Query Request Handler that accepts the input model and returns the output model

//GetCragRequestHandler provides an interfaces to handle a GetCragRequest and return a *GetCragResult type GetCragRequestHandler interface { Handle(query GetCragRequest) (*GetCragResult, error) }

Application Services

The application layer also defines a package, notification for the only application service, notification.Service.

// Notification provides a struct to send messages via the Service

type Notification struct {

Subject string `json:"subject"`

Message string `json:"message"`

}

// Service sends Notification

type Service interface {

Notify(notification Notification) error

}

Interesting Points

- Note that each command/query implements the required functionality using the interface of the required domain/application service

- Query and Command Handlers have a concrete implementation of their Handler interface.

- The only reason for declaring an interface for each handler is to promote easier testing through mocks

- Since each handler corresponds to a unique use case, we do not expect multiple implementations of this interface

- Each use case is tested in isolation with unit testing by mocking the external dependencies focusing on the operation’s logic.

- The

notification.Serviceis an application service since it does not interact with the domain.- The application layer defines just the interface required. The implementation of this interface is the responsibility of the infrastructure layer since it is not part of the business logic.

Dependencies/Interaction with other services

The application layer depends on domain entities and services and uses the crag.Repository domain service to interact with the data storage service, in Go Climb.

Infrastructure

❇️ Important Update (2024)

In the original version of this post, the infra layer consisted of two sub-layers: inputports, and interfaceadapters.

In this updated version I’ve opted for a simpler version that groups all inbound handlers and interface providers under a single layer.

*Besides simplicity, there are cases in which a provider can act as both an inbound handler and an outbound provider. Message brokers can fit into that use-case. For example Kafka can be used as an inbound communication handler that accepts messages and a message publisher.

├── infra

│ ├── http

│ │ ├── crag

│ │ │ ├── handler.go

│ │ │ └── handler_test.go

│ │ └── server.go

│ ├── notification

│ │ └── console

│ │ ├── notificationservice.go

│ │ └── notificationservice_test.go

│ ├── services.go

│ └── storage

│ ├── memory

│ │ ├── repo.go

│ │ └── repo_test.go

│ └── mysql

│ └── repo.go

Interface Providers

Interface services contain the implementation of domain and application services. In our case, these are the crag.Repository and the notification.Service, respectively.

The crag.Repository is implemented by memory.Repo, a repo that holds all data in memory.

package memory

import (

"fmt"

"github.com/google/uuid"

"github.com/pkritiotis/go-climb/internal/domain/crag"

)

//Repo Implements the Repository Interface to provide an in-memory storage provider

type Repo struct {

crags map[string]crag.Crag

}

//NewRepo Constructor

func NewRepo() Repo {

crags := make(map[string]crag.Crag)

return Repo{crags}

}

//GetByID Returns the crag with the provided id

func (m Repo) GetByID(id uuid.UUID) (*crag.Crag, error) {

crag, ok := m.crags[id.String()]

if !ok {

return nil, nil

}

return &crag, nil

}

...

The notification.Service is implemented by console.NotificationService. This service prints notifications in the console.

package console

import (

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"github.com/pkritiotis/go-climb/internal/app/notification"

)

// NotificationService provides a console implementation of the Service

type NotificationService struct{}

// NewNotificationService constructor for NotificationService

func NewNotificationService() *NotificationService {

return &NotificationService{}

}

// Notify prints out the notifications in console

func (NotificationService) Notify(notification notification.Notification) error {

jsonNotification, err := json.Marshal(notification)

if err != nil {

return err

}

fmt.Printf("Notification Received: %v", string(jsonNotification))

return nil

}

Inbound Communication Handlers

In Go Climb, the input/requests are provided through HTTP. The handler of this RESTful API is implemented by crag.Handler.

package crag

import (

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"github.com/google/uuid"

"github.com/gorilla/mux"

"github.com/pkritiotis/go-climb/internal/app"

"github.com/pkritiotis/go-climb/internal/app/crag/commands"

"github.com/pkritiotis/go-climb/internal/app/crag/queries"

"net/http"

)

//Handler Crag http request handler

type Handler struct {

cragServices app.CragServices

}

//NewHandler Constructor

func NewHandler(app app.CragServices) *Handler {

return &Handler{cragServices: app}

}

[..]

//CreateCragRequestModel represents the request model expected for Add request

type CreateCragRequestModel struct {

Name string `json:"name"`

Desc string `json:"desc"`

Country string `json:"country"`

}

//Create Adds the provides crag

func (c Handler) Create(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var cragToAdd CreateCragRequestModel

decodeErr := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&cragToAdd)

if decodeErr != nil {

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusBadRequest)

fmt.Fprint(w, decodeErr.Error())

return

}

err := c.cragServices.Commands.CreateCragHandler.Handle(commands.AddCragRequest{

Name: cragToAdd.Name,

Desc: cragToAdd.Desc,

Country: cragToAdd.Country,

})

if err != nil {

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusInternalServerError)

fmt.Fprint(w, err.Error())

return

}

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

}

The crag.Handler performs the following steps:

- Receives requests and parses their body using the corresponding request model.

- Maps request model to application model (command/query request model).

- Executes the request handler.

- Gets the result of the request handling and returns the corresponding status.

Dependencies/Interactions with other layers

The infrastructure components in Go Climb depend on both the application layer and the domain layer.

- They implement application and domain services(interfaces). The infrastructure layer does not use the

crag.Repository. - They use application query and command request handlers to perform request-based operations.

Bootstrapping - Wiring

Great, the application is structured using clean architecture guidelines. How or where do we instantiate the concrete implementations of interfaces?

Since everything is/should be using an interface for external operations, we need to bind interfaces to concrete implementations and wire the whole application. This place is the entry point of the application, which in Go is main.

func main() {

infraProviders := infra.NewInfraProviders()

tp := time.NewTimeProvider()

up := uuid.NewUUIDProvider()

appServices := app.NewServices(infraProviders.CragRepository, infraProviders.NotificationService, up, tp)

infraHTTPServer := infra.NewHTTPServer(appServices)

infraHTTPServer.ListenAndServe(":8080")

}

main is responsible for getting the external configuration, if any, instantiating the infrastructure services based on this config and passing them over to the application and domain layer to instantiate their structs.

Per Layer Wiring

In this sample application, we also have a per layer entry-point ([app|infra]/services.go) file. This entry point bootstraps the layer dependencies in a grouped manner to avoid bloating main with layer-specific code.

This separation is also applicable in the domain layer and would help if we had multiple domain services.

However, this might be an anti-pattern for more complicated projects since the Services struct exposes all contents of each layer, which is against the least knowledge principle.

Dependency Injection Containers

In many programming languages, mainly OO, it is common to use Dependency Injection Containers for bootstrapping the application. Containers offer automatic instantiation of concrete implementation and binding to the corresponding interfaces. There are some implementations of auto dependency injection approaches in Go that are not covered in this post. However, one of these approaches might be introduced at a later stage in Go Climb.

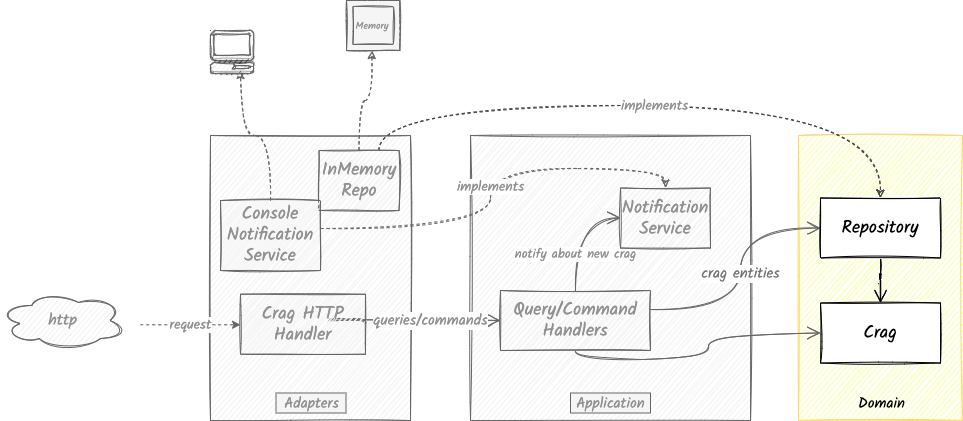

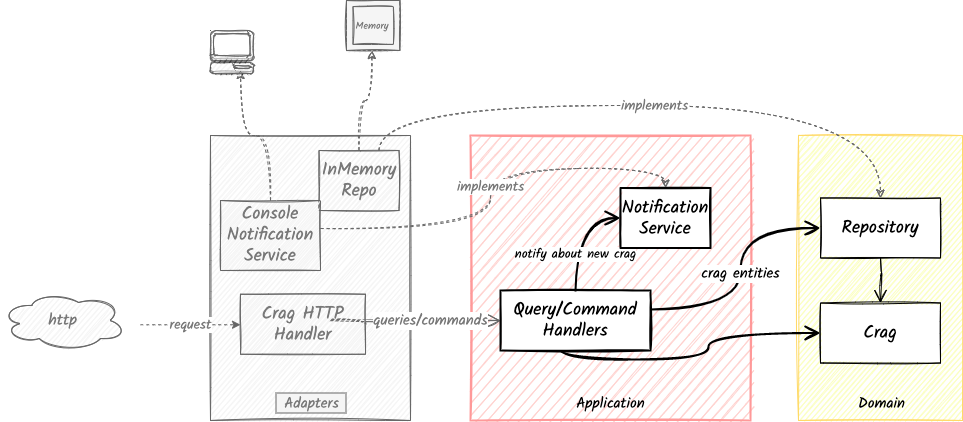

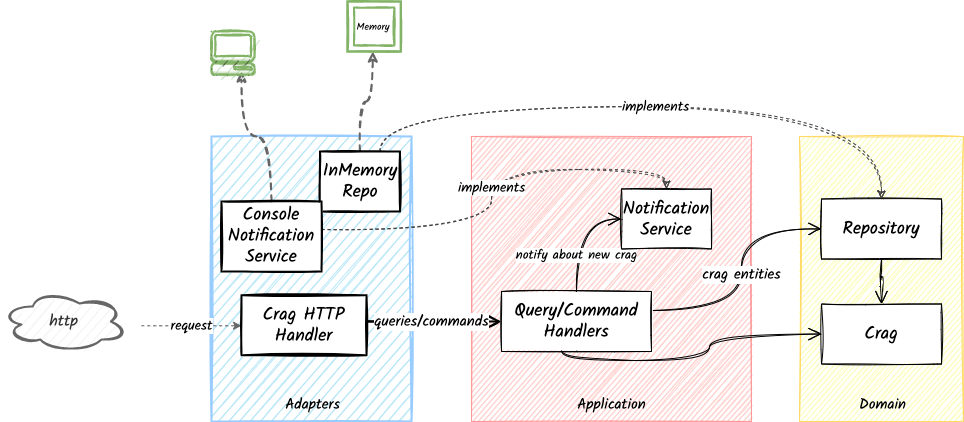

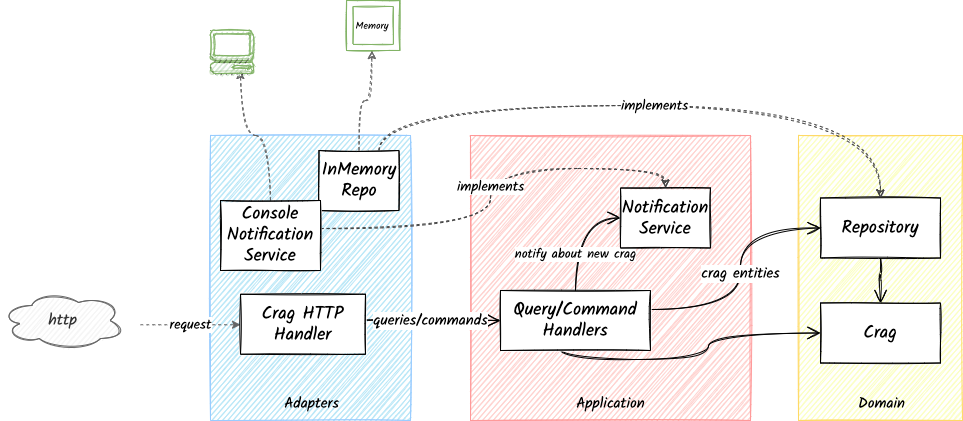

Complete Dependency Diagram of Go Climb

The following diagram contains the complete picture of clean architecture in Go Climb through the separation of domain, application, and infrastructure layers.

Noteworthy Patterns, Principles, and Properties

We have seen the implementation of a simple web app in Go following the clean architecture concept. We now have a good understanding of how components are structured and some of the benefits we can get from this.

While structure allows us to group components cleanly, we can use a few software patterns to make the implementation more robust and promote further decoupling.

Let’s dive into some interesting patterns and properties of the implementation.

Data Contracts

We refer to the agreed interaction model between two components that belong in separate layers by data contracts.

For example, when we need to call a method from an HTTP handler, we need to somehow pass the required data through a model to the application layer’s command/query handler to handle the request. This model is the application data contract.

While not consistently enforced for simplicity, it is a good practice to interact with external layer components through dedicated layer contacts. Applying this in the application layer means that application services expose their operations by accepting their own maintained models rather than receiving domain entities.

Dedicated layer contacts offer a couple of benefits:

- They provide an extra level of decoupling that can be proven helpful when something changes within the application layer but not the domain layer or the opposite.

- This strategy also follows the least knowledge principle since it exposes only the required data in the contract.

Example: The add crag HTTP handler does not need to know about thecreatedAtfield ofdomain.Crag, and therefore a subset of the fields of thedomain.Cragis provided as a different application model asAddCragCommand

Dependency Injection

Another vital detail to note in this implementation is the usage of Dependency Injection throughout the whole application.

All external struct dependencies are provided during the instantiation of a struct as constructor parameters. This practice enables injecting any concrete implementation without needing to care about instantiating the objects within the business logic of an operation nor handling their lifetime.

Example from getCragRequestHandler:

type getCragRequestHandler struct {

repo crag.Repository

}

//NewGetCragRequestHandler Handler Constructor

func NewGetCragRequestHandler(repo crag.Repository) GetCragRequestHandler {

return getCragRequestHandler{repo: repo}

}

Injecting dependencies as interfaces instead of concrete structs has the following benefits:

- We don’t need to maintain implementation details that might change in the future.

- It is much easier to test interface injected parameters through mocks.

Use Cases - CQRS + Isolated Request Handling

As we saw before, the application layer is responsible for implementing the business logic of the services.

Go Climb uses the Command Query Responsibility Segregation pattern, which splits all use cases into queries and commands. 4.

This pattern has the following benefits:

- Queries can read from a read-efficient repository, while commands can write to a repository dedicated to writing operations. This separation can significantly improve performance in high traffic distributed systems 5.

- Since query/command handlers are isolated, they depend only on services they require access to. For example, updating a crag does not require access to the notification service, while adding a crag does. This benefit would be demonstrated even better if we separated read and write repository operations in different interfaces.

- Troubleshooting a use case becomes much more manageable. Developers can check the entire logic of a use case by focusing on a specific query or command without affecting any other code.

Testing

- The application layer and domain layer are tested only by unit tests. This makes it easy to cover edge cases and focus on the application’s core logic instead of integrating external services.

- Depending on the nature of the provider implementations, tests in this layer include mainly integration tests. Unit tests are also applicable if providers contain non-basic application flows.

Maintenance

So we have designed the application using the clean architecture philosophy. Which files do I need to add/change to add a new requirement? Where do I need to look if something is buggy? Let’s explore some scenarios that cover the above questions given our existing codebase.

Adding new requirements

Product Owner: Here is a new requirement

Great, a new requirement; we must be getting good traction :).

- Scenario A: A new business requirement, as in, a new feature, is a new use case

- Is the domain covering the requirements of the application? If not, add the required domain entities/services

- Add a new use case: Add a query when returning some requested data or command when modifying something or triggering an action.

- Add the corresponding provider to implement the new services, if any.

- Scenario B: A new infrastructure requirement like the need for data persistence since in-memory storage is not reliable

- Touch only the infra layer: Add a new implementation of the

crag.Repositoryinterface using MySQL, for example - Rewire main to instantiate the MySQL repository by passing the required configs

- If we need to deploy different instances with different repositories, keep both implementations and introduce a factory pattern to instantiate the corresponding repo based on configuration

- Touch only the infra layer: Add a new implementation of the

Troubleshooting

QA Colleague: I found a bug!

Nothing is bulletproof; let’s use clean architecture’s clear dependency boundaries to find that bug easily!

- Check the application use case - query or command in the application layer - that produces the bug.

- Do the test cases cover the erroneous scenario?

- Yes - check if the test cases are correct

- Yes - Check the infrastructure layer.

- No - Fix the tests and revalidate

- No - add a new test case and revalidate.

- Yes - check if the test cases are correct

- Do the test cases cover the erroneous scenario?

- If the bug is not caused by logic written within the application layer:

- Do the unit/integration tests within the infrastructure layer cover this scenario?

- Yes - check if the test cases are correct.

- No - add corresponding test cases and validate the results.

- Do the unit/integration tests within the infrastructure layer cover this scenario?

Thoughts

This section contains some thoughts related to my observations on the adoption of Clean Architecture in Go and the proposed implementation structure.

On Clean Architecture adoption in Go

Before writing this post, I did read quite a few articles on clean architecture in Go. Many of them receive criticism of the nature “this is OO written in Go, don’t do it”. Another common argument is that clean architecture complicates things by introducing overhead. As per Go’s philosophy, applications should be simple.

Is it against Go’s simplicity philosophy?

I am very new to the language and, therefore, cannot judge these comments based on experience. However, I can understand that each language has its purpose, and especially Go, a very opinionated language, promotes a specific way to build applications. Therefore converting OO code in Go is a mistake. Go simply follows a different paradigm.

In addition, there are indeed cases in which clean architecture might be overkill. This is especially true if we refer to small-sized or limited-scope applications.

On the other hand, definite opinions on such matters are often blind-sighted by exploring unique use-cases. Enterprise applications usually have a broad scope and expect long series of changes through their lifetime. In this category of applications, complexity is inevitable. Rules are necessary to control complexity and allow flexibility when change is required.

A well-tested design philosophy

Clean architecture is heavily tested in the enterprise industry and has passed with flying colors. I have seen it transforming development teams and increase their efficiency dramatically.

Considering the benefits of separation of concerns and the level of maintainability, I believe clean architecture can offer great value when building a broad category of applications, which justifies the small sacrifice of less simplicity.

On project structure

One of the debatable decisions when implementing clean architecture in Go is the package structure approach. In this article, the implementation follows the group-by-layer approach in combination with the group-by-feature approach. As explained above, I think this approach is intuitive and beneficial for defining clear boundaries and giving a sense of direction of dependencies through structure.

Group by feature or Group by layer?

Many gophers consider a pure group-by-feature approach to be more idiomatic by having the benefit of understanding what a program does through a flat structure overview. However, since layers are not explicitly defined through packages, I would argue that developers face high levels of uncertainty when deciding where to add and wire new code.

Some attempts to apply clean architecture in Go follow a pure group-by-layer approach. They group components into layers, and then each layer into packages based on clean architecture terms: services, entities, etc. This is a typical structure you find in OO languages. These projects have received some criticism from the Go community, and I agree. Structuring applications on the three main layers and then package their components by type can make things less clear.

Why not both?

The approach demonstrated in this article, though, I believe, can have its place when implementing clean architecture since it follows a hybrid approach that offers the best from both worlds. This approach provides a valuable benefit that’s missing from the pure group-by-feature; the benefit of understanding components’ concerns and dependencies through a quick look at the structure. At the same time, it still maintains the benefit of feature grouping within each layer.

I believe that the group-by-feature approach for the vast majority of Go applications is the way to go. For clean architecture, though, in my opinion, the hybrid group-by-layer + group-by-feature would be the cleaner option. But I genuinely believe that the readability benefit can be compensated by thoughtful structuring within the domain, application, and infrastructure packages.

Conclusion

As we have seen in this article, Clean Architecture is a powerful software concept. We can use its guidelines to design applications with separation of concerns and offer high maintainability.

Implementing clean architecture in Go, is not complicated but requires some attention. As in every programming language, developers have to follow its rules to maintain its benefits. A proper project and package structure can help developers reduce uncertainty when maintaining a codebase that follows clean architecture.

In addition, Go offers the tools to apply software design principles such as dedicated contracts, dependency injection, and CQRS idiomatically. These patterns work great with clean architecture to increase troubleshooting efficiency, extensibility, and code clarity significantly.

References

-

Head First Design Patterns, Book by Elisabeth Freeman and Kathy Sierra ↩

-

Clean coder blog post on Clean Architecture by Uncle Bob Martin ↩ ↩2

-

Database Scaling with Read/Write split

MySQL Scale-Out approach for better performance and scalability as a key factor for Wikipedia’s growth ↩

![Clean Architecture in Go [2024 Updated]](/assets/images/clean-architecture-in-go.png)

Leave a comment